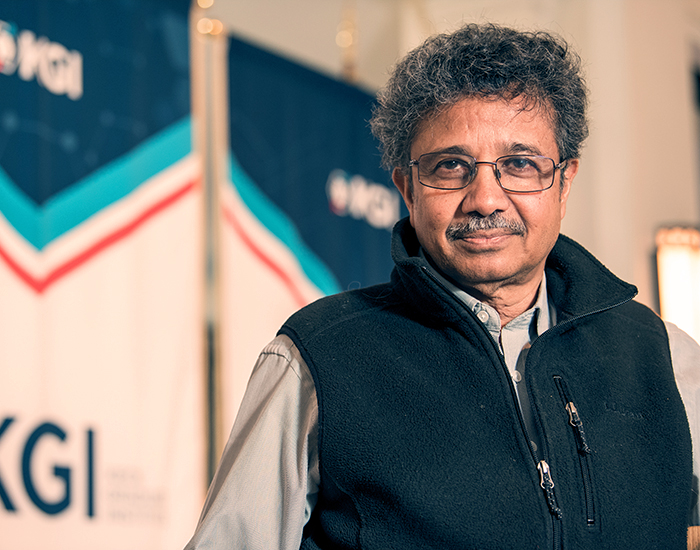

Keck Graduate Institute (KGI) professors often study clinical trial results and sometimes organize these trials themselves. Still, Professor Animesh Ray got firsthand experience as a trial participant when he volunteered for the COVID-19 vaccine trial along with his wife in early September. Although he won't know whether he received the placebo or the actual vaccine until March, his experience has been informative.

Ray's wife experienced a sore arm after receiving the first injection, while he felt nothing. However, nearly two weeks later, Ray developed a sudden chill and violent fever.

He does not believe it was a side effect from the vaccine, as generally, side effects occur within 24 to 72 hours. Instead, he feared that he had COVID.

Thankfully, Ray tested negative for the virus, and the fever went down by the next day. He thought perhaps he had gotten the stomach flu.

Twenty-one days later, he received the second shot, with no reaction. Then, exactly two weeks later on the dot, he experienced exactly the same situation, this time with shivering and a higher fever, which went up to 102 degrees within three and a half hours.

His oxygen saturation also declined rapidly. Again, by the next day, he was fine, and he tested negative for the virus.

"These two bizarre symptoms exactly two weeks after both the first and the second shots could be an adverse effect, but it could be completely coincidental," Ray said.

Regarding general vaccine safety, one concern is that the vaccine might cause patients to contract the virus it is intended to prevent. For example, the polio vaccine, which was derived from a live virus, did cause some individuals to contract polio, though at a low enough rate not to offset the benefits of the vaccine.

“It is impossible to contract COVID-19 from the RNA vaccines because these vaccines are based on the genetic codes of only one of some 29 different proteins encoded by the whole SARS-CoV-2 virus," Ray said. "There could, however, be other adverse effects. You have to weigh the beneficial impact that the vaccine is going to have for many people to the adverse impact that it can have on the life of one or two individuals."

The second concern regarding vaccine safety is that it will facilitate further infection by the same causative organism. While some scientists believe that certain vaccines against dengue might produce this effect, the evidence is still open to debate for dengue, and there is no evidence that the same might occur for COVID-19 vaccines.

While Ray believes that the second concern is theoretically possible, he concluded that the risk is exceedingly low after reviewing the literature on the topic.

"In my evaluation, the vaccine produced near-zero risk."

"However, one of the major considerations is that using non-protein substances such as RNA as a vaccination agent could lead to a hypersensitive reaction or interferon response," said Ray

When RNA is injected into the human body, it immediately triggers a defense mechanism in cells. For this particular vaccine, a very large bolus of RNA is injected, and the response can be similar to the symptoms Ray experienced: chills followed by a sudden difficulty in breathing and a choking sensation.

In very severe cases, the individual may experience intense inflammation and ultimately coma and death. However, the COVID vaccines do not contain pure RNA but modified RNA.

"I read the literature on the effects of RNA modifications in various animal studies, and it was quite clear that these modifications most likely to be used in the vaccines have a very low chance of massive interferon response," Ray said.

Similar results were found from Phase 1 clinical trial data in which healthy volunteers were injected with the RNA. Although cases of interferon responses may increase as the number of people receiving the vaccine increases, Ray still believes that the percentages will be low.

Upon hearing from Ray about his experience, one of Ray’s past students who was a KGI graduate in the school's early days—and also a physician—stated that Ray’s possible adverse reaction to the vaccine, if not purely coincidental, appeared rather mild relative to the risk of contracting COVID-19. Ray agrees.

For Ray, his motive for participating in the trial was a personal one. In the past, vaccines have used materials such as proteins, which directly cause antibodies' production.

"I've been a molecular biologist nearly all my life," said Ray. "This is a major fruit obtained from numerous breakthroughs in fundamental discoveries of molecular biology, where information—which is an abstract concept—is transferred to cells, leading to biological properties or phenotypes and eliciting the antibody response. This is the first time a person is being primed with mere information to produce a vaccine."